We have heard the phrase “grim milestone” so often in the past year that it now falls into the realm of journalistic cliché. Monday’s news that the US has surpassed half a million Covid-19 deaths should not, however, be any less poignant for its morbid familiarity.

These are the moments in which individual and shared grief intersect. But as we struggle to take stock of societies’ losses, what does coming to terms with grief, as a culture, really look like?

Whether portraying others’ grief or revealing their own, artists are often able tap into something universal. One need not be Christian to feel Mary’s anguish in Renaissance depictions of Christ’s crucifixion; one need not have lived through the Spanish Civil War to feel the harrowing abyss at the heart of Picasso’s “Guernica” (pictured above). The torment of Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” is clear to all.

The New Museum in New York City explores this idea of processing grief through art with painfully appropriate timing. Just days before Monday’s Covid-19 milestone, it opened the new exhibition, “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America.” In another cruel twist, the show’s mastermind, Nigerian curator and critic Okwui Enwezor, died before its opening following a long battle with cancer.

Rashid Johnson’s “Antoine’s Organ,” brings together lights, plants and various objects within a black steel frame. Credit: Rashid Johnson/Hauser & Wirth

The show was, however, conceived before the emergence of Covid-19. (Enwezor passed away in 2019, though he might well have predicted how a pandemic would disproportionately affect people of color.) It instead addresses racial injustice and, in the late curator’s words, “black grief in the face of a politically orchestrated white grievance.”

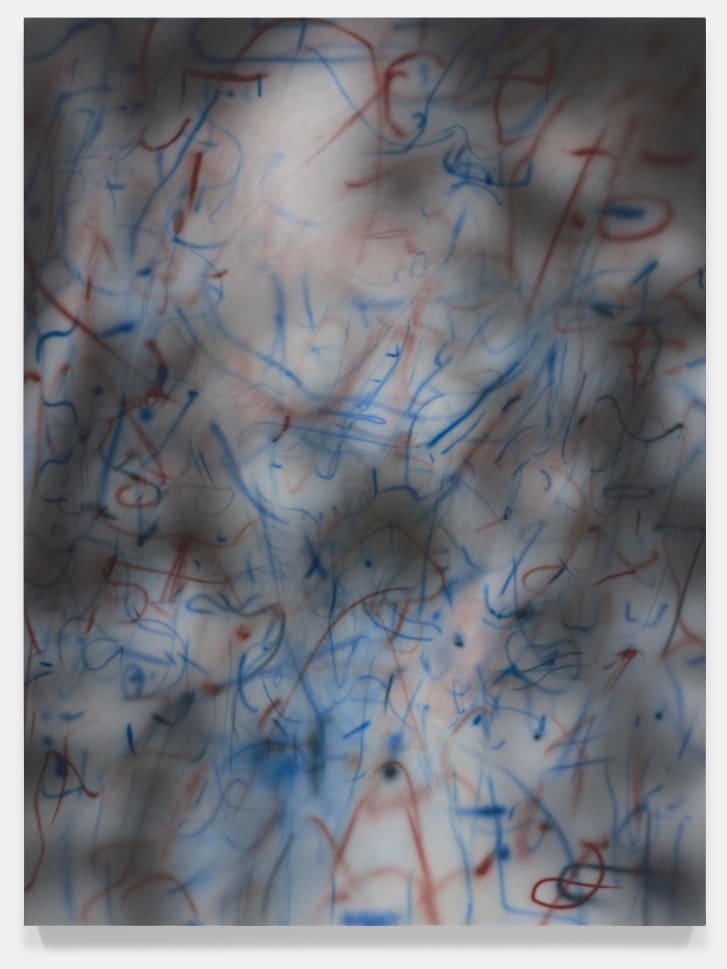

In the exhibition, memorial and commemoration take many forms. In “Peace Keeper,” Jamaican artist Nari Ward covered a full-size hearse in tar and feathers. Rashid Johnson’s living installation, “Antoine’s Organ,” meanwhile presents plants and various household items (including shea butter and books chronicling the experiences of the African diaspora) in a commentary on the nature of life and decay. Elsewhere, LaToya Ruby Frazier’s photographs of working-class hardship and Julie Mehretu’s abstract landscape paintings all struggle with loss in their own unique ways.

The original version of Nari Ward’s installation “Peace Keeper,” pictured at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1995. Credit: Nari Ward/Lehmann Maupin/Galleria Continua

These varied responses to the show’s central premise — that grief is irrevocably woven through the Black experience in America — are both personal and, by virtue of their exhibition, inherently public. Artistic creation is often an act of both private catharsis and solidarity.

Julie Mehretu’s painting “Rubber Gloves (O.C.).” Credit: Julie Mehretu/White Cube/Marian Goodman Gallery/Tom Powel Imaging

Source:https://edition.cnn.com/